This article explores the education crisis and cultural norms in South Sudan with a focus on: the 2020/2021 primary school end-of-course examinations conducted in February 2021; the return of young mothers to school and ways to increase enrolment, especially of girls but also of boys; and the growing insurgency.

Primary school leaving exam practices

According to the latest national education statistics from 2016, there are 4,950 primary schools in South Sudan with a student population of 1,098,292 learners. According to the Ministry of General Education’s statement in February 2021, a total of 75,000 primary school learners were registered for this year’s PLE examinations. This was far less than the expected number. In related news, 908 learners in seven centres missed the examinations due to access problems and security-related issues. Fourteen areas were reported for security concerns (e.g. Nasir with 98 students, Longechuk with 220 students, Akobo with 61 students, Fangak with 223 students, Ayod with 109 students, Nyiror with 141 students and Tonj East with 154 students; other areas were not mentioned).

Most of these areas are believed to have a strong presence of SPLA-IO (Sudan People Liberation Army in Opposition) forces, a former rebel group that fought the government between 2013 and 2018. However, the SPLM-IO is now part of a coalition or unity government in Juba.

Final exams have been ordered for these places retrospectively.

What do we learn from these experiences?

For one thing, it is costly to schedule another round of exams for the places where the exams were missed. For another, quality is compromised because these learners were assumed to be in difficult locations, so the exam content was relaxed. The public might also develop some doubt about the preference if the places where it was relaxed are the homes of the examinees.

Most states, with the exception of Juba City, are affected by conflict and learners have not been taught well to cover the curriculum. In the picture on the left, teachers talk to learners at William Chuol Primary School in Fangak, Jonglei State in 2020 about the exam. The students were unsure about what content might be asked for in the exams. The appearance of the teachers does not speak for their quality. This means that both learners and teachers were desperate or afraid of conflict breaking out as Fangak town or Jonglei State is one of the states with frequent attacks and still poses more risks today. The revitalised government must proceed with urgency and explore every possible solution for peace to ensure that all children in Primary 8 next year and other classes, regardless of location, can start their exams as scheduled. Peace is urgently needed so that the people of South Sudan have better and quality practices for health, education, road construction, agricultural services, among others, for a better livelihood.

Most states, with the exception of Juba City, are affected by conflict and learners have not been taught well to cover the curriculum. In the picture on the left, teachers talk to learners at William Chuol Primary School in Fangak, Jonglei State in 2020 about the exam. The students were unsure about what content might be asked for in the exams. The appearance of the teachers does not speak for their quality. This means that both learners and teachers were desperate or afraid of conflict breaking out as Fangak town or Jonglei State is one of the states with frequent attacks and still poses more risks today. The revitalised government must proceed with urgency and explore every possible solution for peace to ensure that all children in Primary 8 next year and other classes, regardless of location, can start their exams as scheduled. Peace is urgently needed so that the people of South Sudan have better and quality practices for health, education, road construction, agricultural services, among others, for a better livelihood.

Young mothers return to school

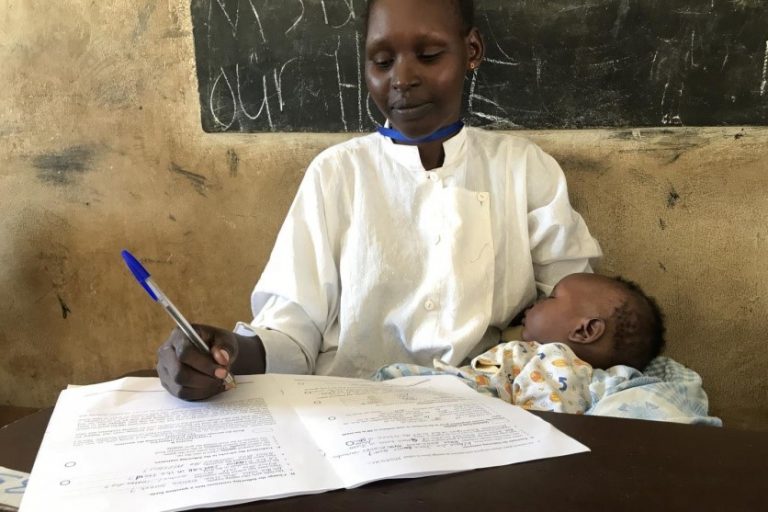

In South Sudan, before COVID-19, over 1.2 million children, most of them girls, were not in school. The protracted conflicts of 2013 and 2016 devastated the country’s education system, and the recent pandemic has further excluded over one million children from school. For girls, COVID-19-related school closures have triggered an increased risk of gender-based violence and exploitation, leading to an increase in child marriages, which affect 51.5 per cent of girls in the country. Many cases of early pregnancy have been recorded, dramatically increasing the risk of dropping out of school.

These girls may never return to school, ultimately limiting their chances of career advancement. For example, more than five girls gave birth during the exam period and were allowed to continue writing their exams. This was a new norm of all girls in a class sitting for the exam, which was not practiced before South Sudan’s independence in 2011. This can be considered a pecedividend.

Despite COVID-19, and despite many students being displaced due to the conflict in South Sudan, one of the students, Nyaget Mot, is coping with life in a Protection of Civilian (PoC) Camp as a determined mother and student. Other important services that help keep girls in school, such as school feeding, extracurricular activities and psychosocial and educational support, have also been disrupted. UNICEF is working with the government and partners to implement the National Strategy for Girls’ Education, which includes advertising, advocacy, marketing, public relations, branding, arts (music, song, dance, theatre) and social mobilisation at all levels to improve girls’ enrolment, retention and promotion. These strategies were considered entertainment to some extent and for this reason the Episcopal Church schools resorted to using the Mothers’ Union in the churches as ‘learning mentors’. These ‘learning mentors’ have several strategies and one of them is to go from house to house and talk to the dropouts and their parents about the importance of these girls going back to school. This has been shown to work on a larger scale, and perhaps this could be a model that the government or other church schools could try by involving their head teachers.

Growing insurgency continues

Despite the 2018 agreement to bring South Sudan’s main warring parties to a ceasefire and unity government, the rebellion in the southern multi-ethnic region of Equatoria continues to grow at a rapid pace. The long civil war is not yet over, as a major insurgency south and west of the capital Juba has plunged large parts of the Equatoria region into chronic violence that has displaced many thousands. Roads leading to the capital Juba and the town of Yei have been closed for most of the last ten days. For example, from late March to early April 2021, a number of conflicts were recorded in Yei district in Payam Otogo in Morsak, Lata, Mudeba, Ombasi settlements and others. These have displaced over 120 families with a total population of over 1550 people. This population left their villages about 20-25 km and took refuge in a camp in Yei, the diocesan headquarters of the Episcopal Church. This was reported to the government and other humanitarian agencies and minimal assistance in the form of non-food items was provided. The church set up a committee tasked with mobilising food items to meet this urgent need. The church is also handicapped because the church doors are closed due to COVID-19 and it is difficult to mobilise funds from the Christians. Besides, the church has received more than four rounds of IDPs after the series of conflicts. In the photo are church, government and community leaders encouraging the IDPs, praying for them and welcoming them to the church compound. Most people in Yei who have relatives who were in this displacement were unable to welcome their relatives due to limited space and inadequate food. This distorted the cultural norms of the people of South Sudan, especially in Yei.

Let those who read this message be ambassadors* of peace for South Sudan and remember us in your various churches and mosques!

By: Lubari Stephen Elioba

By: Lubari Stephen Elioba

Director of the Education Programme

Episcopal Church of South Sudan

Department of Education and Training

Juba, April 2021